[ad_1]

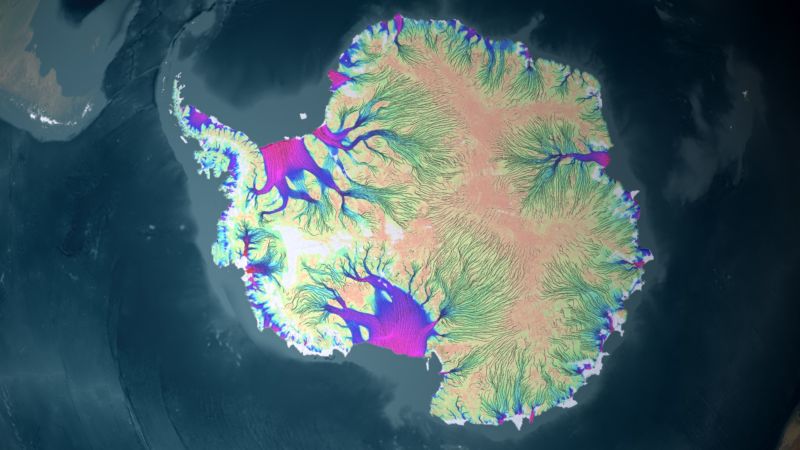

Enlarge / Velocity of recent ice flow around Antarctica. Thwaites Glacier is one of the smaller purple regions on the left side of this image. (credit: https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/3849)

Glaciers are moody things with a myriad of personalities. Some are pretty stubborn, refusing to melt too much as Earth’s climate warms. But others are quite sensitive, with the potential to shrink more than you might expect if you push them too far.

Much of this has to do with the shape of the bedrock beneath. Some glaciers that touch the ocean have bedrock bases that slope downward as you head inland. If the glacier starts retreating downhill, seawater can flow in and float the ice more and more easily, destabilizing it so it retreats faster.

Each marine glacier has a “grounding line”—the point where ice stops resting on solid ground and starts floating, instead, like a canoe shoving off from shore. When you hear about an “ice shelf,” that’s the floating portion of the glacier. The position of the grounding line along the bedrock is where topography plays such a big role. But a new study from a team led by NASA’s Eric Larour shows how the bedrock can move, too, making these sensitive glaciers a little less sensitive.

Read 8 remaining paragraphs | Comments

[ad_2]

Source link

Related Posts

- What to know about measles in the US as case count breaks record

- NASA to perform key test of the SLS rocket, necessitating a delay in its launch

- Fiber-guided atoms preserve quantum states—clocks, sensors to come

- Trump administration puts offshore drilling expansion in Arctic, Atlantic on ice

- The antibiotics industry is broken—but there’s a fix