[ad_1]

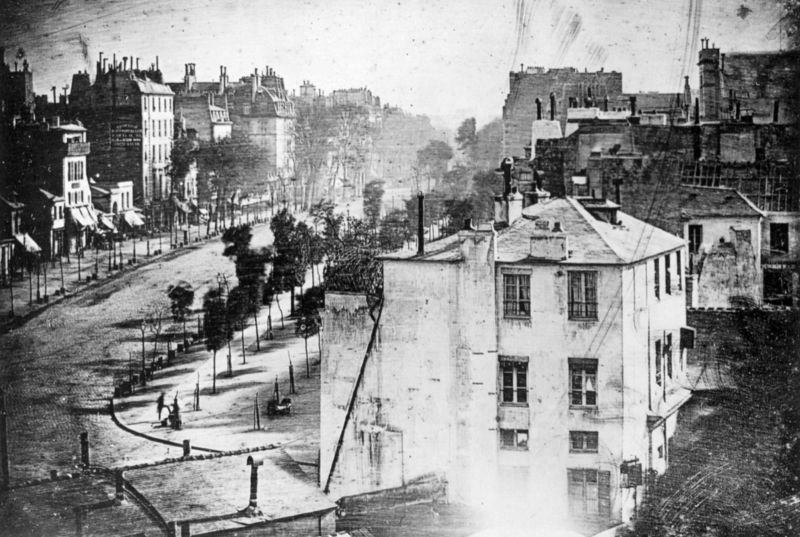

Enlarge / The earliest reliably dated photograph of people, taken by Louis Daguerre one spring morning in 1838. (credit: Public domain)

Daguerreotypes are one of the earliest forms of photography, producing images on silver plates that look subtly different, depending on viewing angle. For instance they can appear positive or negative, or the colors can shift from bluish to brownish-red tones. Now an interdisciplinary team of scientists has discovered that these unusual optical effects are due to the presence of metallic nanoparticles in the plates. They described their findings in a new paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Co-author Alejandro Manjavacas—now at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque—was a postdoc at Rice University, which boasts one of the top nanophotonics research groups in the US. That’s where he met his co-author, Andrea Schlather, who ended up in the scientific research department at the Metropolitan Museum of New York. The Met has a valuable collection of daguerreotypes, and her new colleagues were keen to find better methods for preserving these valuable artifacts.

Schlather contacted Manjavacas and suggested this might be a great place to apply their combined expertise in nanoplasmonics—a field dedicated to detailing how nanoparticles interact with light. Think of it this way: light is an optical oscillation made up of photons. Sound is a mechanical oscillation made up of quasiparticles known as phonons. And plasma (ionized gas, the fourth fundamental state of matter) oscillations consist of plasmons. Surface plasmons play a critical role in determining the optical properties of metals in particular.

Read 14 remaining paragraphs | Comments

[ad_2]

Source link

Related Posts

- What to know about measles in the US as case count breaks record

- NASA to perform key test of the SLS rocket, necessitating a delay in its launch

- Fiber-guided atoms preserve quantum states—clocks, sensors to come

- Trump administration puts offshore drilling expansion in Arctic, Atlantic on ice

- The antibiotics industry is broken—but there’s a fix